posted by on November 30, 2024

I arrived in Auckland at 6am local time and was determined to not sleep the first day of my trip away. After checking out the waterfront and the Sky Tower, it began to drizzle, which timed pretty nicely with our plan to visit the Auckland Art Gallery (AAG), a moderately large, public, free art gallery that’s open every day in the heart of the city. The closest I’ve come to this level of convenience in going to museums was when I lived in NYC and could go to the Met for free.1

From my experience with art museums, especially on the East coast of the US, I was expecting to see art from old Europeans chronicling the first times Europeans had interacted with the land or with the people who were already there. I planned on rolling my eyes at language around “tradition” and nationalism, the same way I would about portraits of the founding fathers in the US.

I remember visiting the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle in mid 2018 and finding an exhibit full of Native American art from local tribes that was tucked away in the basement where it seemed like the average visitor would have missed it entirely. Maybe that’s changed since the renovations finished in late 2018, but I haven’t been back. So much of what I’ve seen of US confrontation of Native American history in museums is having relegated space far from the main entrance where it feels quietly acknowledged just how poorly the Native Americans have been treated over the centuries. Even the American art wing of The Met does this, to some extent. Look at how far into the exhibit you have to go to reach Native American art:

What I found at AAG was vastly different, which is part of a broader continuing theme I’ve written about where my assumptions were wrong. Here, as in other places around Auckland and the rest of the country, there was English and Māori written text side-by-side, and it felt like history that the country was willing to discuss openly, warts and all. I found that admirable and a nice change of pace.2

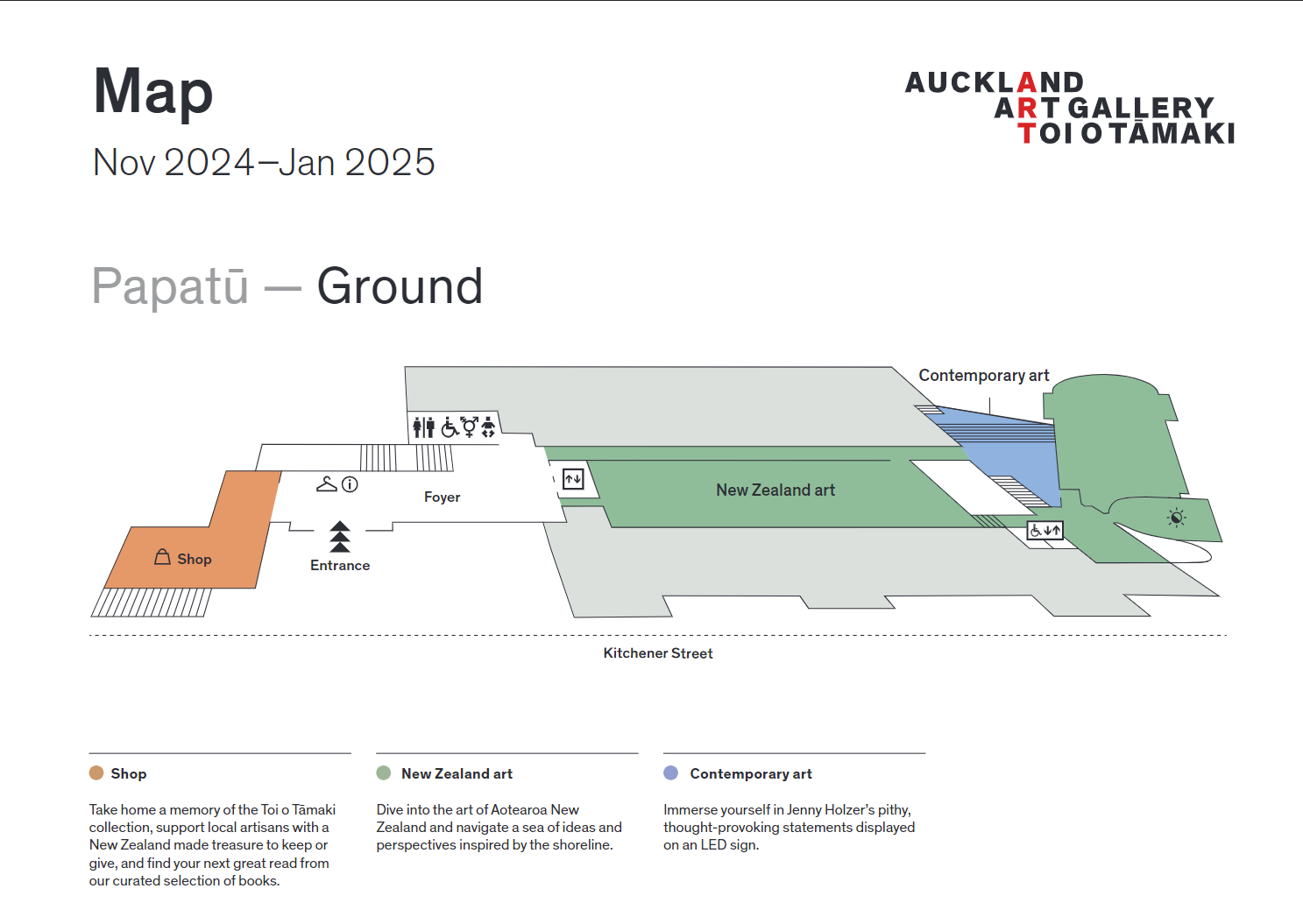

I unfortunately didn’t take many pictures of the gallery space itself, but I was able to download the online map of the building. As you enter the gallery, you enter the green area below of Aotearoa New Zealand Art and are immediately confronted with several pieces spanning topics of ecocentrism, celebrating the landscape of New Zealand, and a birds-eye video of someone humming what I assume is a Māori tune while rowing a boat.

It seems impossible to me to go to this gallery and not come away with some understanding of the influence of Māori culture on NZ history, and I think that’s incredbly cool.

Once I realized this contrast to my experience of US museums, I began keeping a closer look out for the intentionality of how the space was arranged and decorated.

An example of this was in the Threads of Time Installation on the Mezzanine floor of the AAG, where this wall had centered an oil painting, Saint Sebastian by Guido Reni (circa 1625).

The details about that painting, provided by the AAG, read:

Forbidden by the Catholic Church from depicting saints with a ‘beauty exciting lust’, Baroque masters of figure painting like Guido Reni found ways to cover their nude subjects without compromising their sensual beauty. Saint Sebastian was a 4th-century Christian soldier who was shot by archers of the Roman emperor Diocletian. As he writhes against a tree, Sebastian’s twisted loincloth sinks under its own weight, suggestively revealing what it is supposedly intended to conceal.

We noticed immediately that the painting to the upper right3, middle right4, directly below5, and the far bottom left6 among others had all been placed in ways such that their subjects tended to look at the center of the wall towards Saint Sebastian. What better way to show the kind of “‘sensual beauty’ that was bordering forbidden-levels of ‘lust’ according to the Catholic Church” than to have so many other paintings on the same wall directing their subjects’ gazes towards him?

This might be a 101-level lesson about art presentation, but it hit my “3-hours of sleep on a 13-hour flight” brain like an incredible epiphany. Your art doesn’t just need to be presented according to which part of Europe nor which century it came from. And even if you do sort it by time period or country or artist, you still have so much control over the physical space the pieces take up. You as a gallery owner could choose to communicate things to the people looking at the art by placing that art within the context of the other art in that same room!

This happened again as we reached the Modern Women: Flight of Time exhibit on the top floor, which had artwork by and celebrating women throughout.

From the plaque beside it:

The underlying messages of A Lois White's mysterious 'female allegories', in which women cavort, dance or simply sway in unison, are often ambiguous. What might the rhythmical Trio, 1943 mean?The answer lies in the artist’s fascination with classical mythology and Renaissance art. Trio is like a modern interpretation of the classical myth of the Three Graces, made famous in such paintings as Botticelli’s Primavera, 1477-82. White depicts the Graces Aglaia (splendour), Eufrosyne (joy) and Thalia (abundance) inside a compressed space, abstracting the goddess’s bodies to construct a play of curves and sharp angles, which interlocked together like the sections of a frieze.

In my opinion, when you put a Trio of women in the wing celebrating the lives, experiences, bodies, etc. of women, and when your Trio of women look like their bodies “construct a play of curves and sharp angles, which interlocked together,” there is no ambiguity. The context of the space answered the question for me.

I look forward to bringing this newfound appreciation of spaces and the contexts they give their art pieces into museums and galleries I travel to in the future. Maybe I should revisit my local city’s one over the next month sometime. I wonder if I can get in for free by being a resident?

Per my previous post, Aotearoa New Zealand has a lot of endemic bird species and I took lots of pictures of them during my travels. This one was the first on my trip, and while it’s not technically endemic, it is only found in the South Pacific. Perched on the lamppost in this picture from Albert Park is the Kōtare | Sacred Kingfisher:

As far as I could tell, the smaller bird soaring in the background is probably a Warou | Welcome Swallow, given the shape of the wings and tail, but I didn’t notice I had even captured it until we had left the city, so there was no way to go back and double-check.

Footnotes

-

Could have gone for free, had I actually gone while I lived there. In my defense, there were only a few non-winter, non-covid months before we fled the city. ↩

-

To date, Columbus Day is still a federal holiday and is celebrated in 36 / 50 states, despite the Biden administration recognizing Indigenous People’s Day in 2021 and being the first presidential administration to do so. ↩

-

Virgin in Prayer by Giovanni Battista Salvi da Sassoferrato (17th Century). ↩

-

The Annunciate Virgin (Santissima Annunziata) by Unknown Artist (17th Century) ↩

-

Study of Holbein’s ‘Dead Christ’ by Tony Fomison (1971-73) after Hans Holbein the Younger ↩