posted by on November 30, 2024

I keep saying “New Zealand has a lot of unique birds” but to really understand why, we have to go back prior to any humans living there. Sure, birds like the Eurasian Blackbird and the House Sparrow were eventually introduced, but there are plenty more species that are native to the area.

This post, I’m going to start with the bird photo instead of ending with it. Here’s a Pūkeko | Australasian Swamphen (endemic to New Zealand and parts of Australia) with two of its chicks that we saw walking around in a public park in Rotorua:

I’m no expert on this history, but from what I’ve read and heard from tour guides, the real history of Aotearoa started back when the Zealandian continent and the Australian continent both broke off from Gondwana some 80 million years ago and then subsequently began breaking apart from each other, finishing around 50 million years ago.

During that time, the K-T major extinction event wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs. Elsewhere in the world, some mammals were able to survive the event, but the story goes that bats were the only surviving land-based mammal of Zealandia.1 All other mammals found today on the islands (sheep, rabbits, humans, cows, dogs, cats, mustelids, marsupials, etc) have been introduced over time, or must have been able to swim long distances in the sea like seals, sea lions, dolphins, and whales. I mentioned previously that the first Māori settlements weren’t until the 1300s, which gives millions of years of time for different types of birds to arrive and evolve.

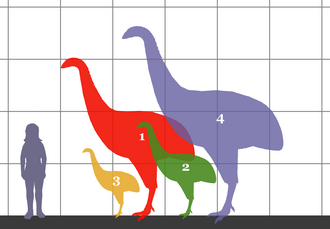

The largest of these birds was the moa: a flightless bird that could grow to be up to 12ft long and 510lbs. It grazed foliage in the bush, leading native trees to evolve to have smaller, denser leaves or tougher, more resistant ones. Moa only had one natural predator: Haast’s Eagle, the largest eagle to have ever lived. When the Māori first landed, they began hunting the moa2 for food, and burning the bush to make room for settlements, which led to the moa going extinct prior to European arrival. Haast’s Eagle also went extinct around that time, since it was so dependent on moa as its sole food source.

When the Māori landed, the polynesian rat came along with them, which led to the eradication of several bird species and several insect species that had never had predators before. Once the Europeans arrived and found land that looked just as farmable as the sprawling English countryside, they decided to bring over the classic English staples: sheep, cattle, dogs, and rabbits. Rabbits, being known for breeding extremely efficiently in good years, wound up reproducing out of control. These rabbits decimated local vegetation and drier areas of the South Island have still not recovered, over 150 years since the boom in rabbit population.

In a sort of “old lady who swallowed the fly” situation, Europeans then brought domesticated ferrets and stoats and weasels to the land in hopes that they’d be able to curb rabbit populations. Despite there being debate about the negative effects these mustelids would have on the local flightless bird populations, a few months later, thousands of mustelids had already been released. The problem was that this ‘natural enemy’ of the rabbit in Europe had found much easier prey: local fauna that had never had natural predators before.3

In addition to this, Australian possums4 were introduced in the mid 1800s for fur trading. Given that they’re also nocturnal omnivores, they competed with local bird populations over food, including over-feeding on local insects, seeds, fruit, and flora, leading to overhwelmingly negative effects for local wildlife.

Among others, the kiwi and kākāpō are examples of birds that evolved on Aotearoa with no natural predators. Whereas moa filled the ecological roles of larger grazing mammals like giraffes, antelope, or bison, the kiwi and kākāpō are nocturnal foraging birds that fill the niches of smaller mammals like hamsters or sugar gliders.5

Kiwi birds have huge eggs6 that are occasionally left in burrows for short amounts of time when the father needs to get food. During this time, stoats will happily come and eat the egg or the chick if it’s young enough that it can’t effectively fight back.

The role of the National Kiwi Hatchery that we went to in Rotorua was to take unhatched kiwi bird eggs, incubate them in the safety of a lab, hatch the birds, vaccinate them against the most common bird-releated diseases, and feed them until they reached a certain minimum size (usually reached in a few months). After that, they were moved to predator free enclosures until they reached another minimum size, at which point they would be safe to be in the wild and could have powerful enough kicks to ward off mustelid attacks. The conservency also puts foot bands on all the kiwis for census reasons and then trackers on the male kiwis, since the fathers are the ones who incubate the eggs in the wild. With this, they’ve been able to grow the wild kiwi populations over the last decade, though there’s still a lot more work to do. I also got to see a couple of day-old kiwis during my visit to the hatchery, which was incredible.

No photos or videos were allowed around the kiwis because their eyes and ears are so sensitive to light and sound. All it takes is one aloof tourist not realizing the flash on their camera is on to do lasting damage.

The kākāpō population fell to a minimum of 49 birds, which means that they’re in a similar problem to cheetahs in terms of low genetic diversity. While all kākāpō currently live in predator-free areas off the coast of the main islands of New Zealand proper, there have been attempts to reintroduce them to the wild as well as sequencing their genome to try and use cloning or CRISPR to eventually improve their genetic diversity in the future.

Today, there’s an ongoing campaign to rid Aotearoa of the three introduced predators representing the gretest threats to local wildlife, called Predator-Free 2050. By 2050, if everything goes according to plan, there will be no more rats, stoats, and possums. This has already gotten underway, and you can see stoat traps on major hikes fairly regularly.

I find it to be a really compelling series of questions, as someone who has never previously owned any fur from an animal that was killed to make the garment: what should the New Zealand citizens do with the caught and killed wildlife as part of this campaign? Would you as a tourist buy wool that has possum fur incorporated into it? Obviously the sheep wasn’t harmed to get the wool, but the possum very much had to die to make the garment. Is protection of endangered species a good enough reason to kill possums? Is it less wasteful to use the animal coats from animals that the government has decided need to be killed for conservation reasons?

Footnotes

-

The discovery of the Saint Bathans mammal fossil indicates otherwise, but I get not changing scripts of tours that started prior ot 2006. ↩

-

Moa is the Māori word for domestic fowl. One of our tour guides figured they named them that way because moa had a similar role to chickens: bird that feeds you. ↩

-

You can read a lot more about the history of this whole situation at https://teara.govt.nz/en/rabbits/print ↩

-

Not to be confused with the American opossum ↩

-

While the kākāpō cannot fly by flapping its wings, it is very good at climing and it can glide or parachute after jumping out of trees, which made me think of sugar gliders or flying squirrels. ↩

-

The single greatest egg-size to bird-size ratio of any bird. They also have the smallest bill of any bird because bills are measured from nostril to tip, and the kiwi bird’s nostrils are practically at the tip of the bill rather than near their face. No other bird’s nostrils are like this. ↩