posted by on May 21, 2025

My partner and I attended a pottery workshop at a studio outside of the city this past weekend. When you do pottery in a city, space is a premium. It’s common to feel anywhere from cozy to a bit claustrophobic in a busy art studio. Most don’t have any outdoor spaces, and even if they did, there would likely be restrictions on how openly you could do alternative firing techniques without creating significant risk to your neighbors or the general public. You can hardly even use outdoor grills in a lot of neighborhoods in my city, even if you have a back deck or patio for them.

For these reasons, we drove an hour to a much larger ceramics warehouse that had a large outdoor firing yard where you could have open flames, smoke clouds, and gas kilns. There, the head of the warehouse ran a Raku firing workshop for the dozen potters and their plus-ones all day. It was sunny with no clouds and was surprisingly windy all day, but it was overall a lovely time.

Raku originated in Japan. There, the piece was removed from the kiln while still very hot and it was left to cool in the open air. Western potters have since adapted this method to put an emphasis on a chemical reduction reaction as part of the firing process. I’ve only experienced the Western version, in which pieces tend to be heated up to hundreds of degrees1 in a gas kiln before being carefully removed and placed into a container2 semi-filled with combustable material.3 There, the hot pieces combust that material and then a lid is placed over the top to starve the environment of oxygen. This oxygen-starving is what causes the reduction reaction, and any exposed clay body is turned completely black. After about 20 minutes of burning in the container, the piece is carefully removed again and stuck into a water bath where it rapidly cools. Finally, the pieces can be polished when they’re cold enough to handle. To achieve the style of crackling glaze effects that Western Raku has become known for, potters will move the hot piece around in the air and/or spray water at it to help encourage the glaze to form cracks prior to the combustion process.

Because Raku involves heating and rapid cooling, it’s common to have pieces crack and shatter. Clay-joins like handles or any inconsistencies in clay thicknesses within the piece can wind up causing undue thermal stress during the cooling process. While these represent formidable risks, they also mean that any Raku fired piece that comes out nicely is that much more precious. Making Raku pottery is high stakes, and you can’t celebrate how a piece looks until it finishes cooling, from my experience.

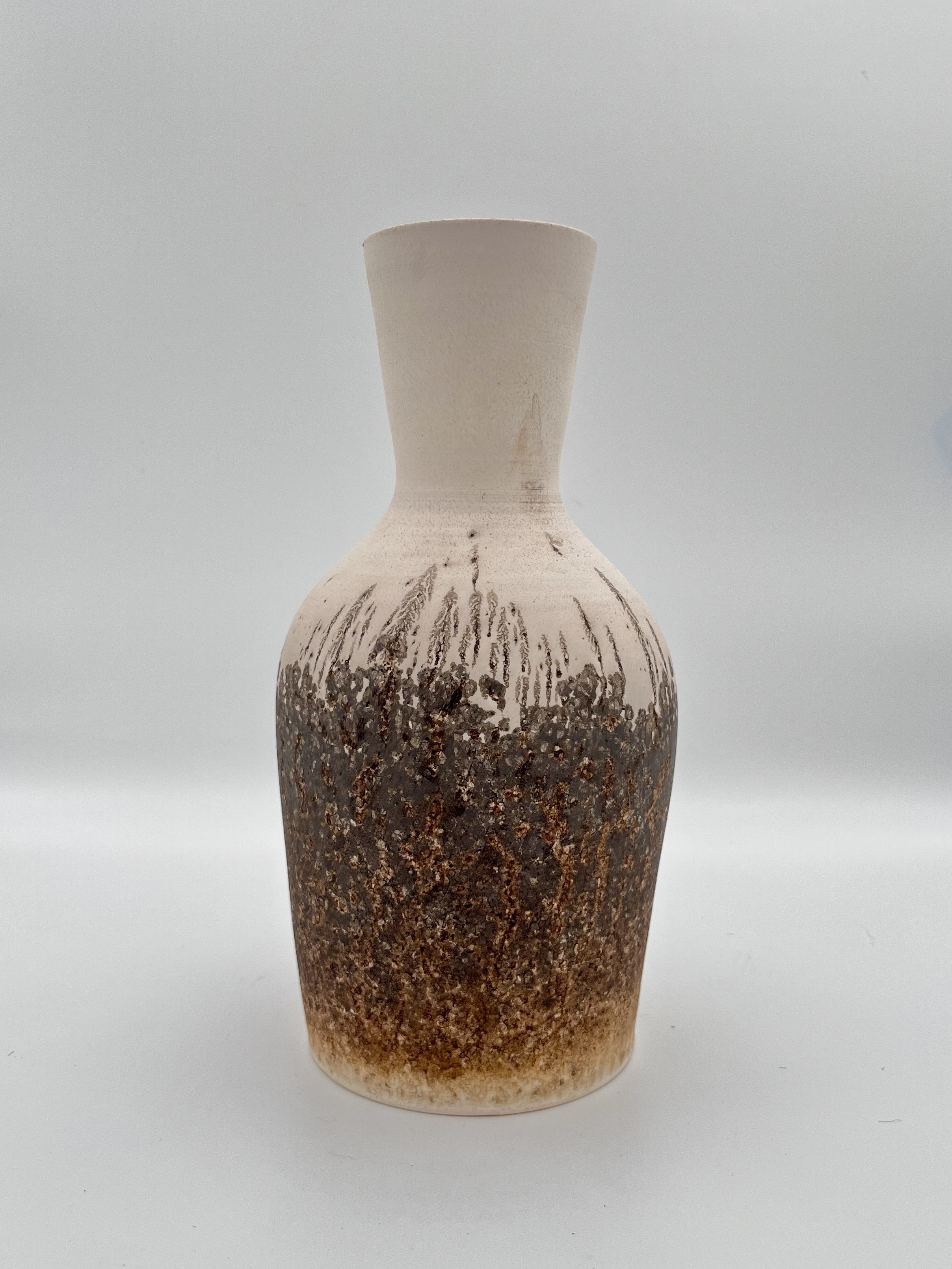

My partner made a handful of vases and sculptures for the event, with the expectation that if any of them survived and looked nice, then the event was a success. All of their pieces wound up surviving, with only one piece producing any new cracks, though those were only surface level. Of those that survived, our favorites were the two that had glossy white Raku glaze that achieved a nice crackle effect, followed by one with a completely different style.

As Western potters developed their own versions of Raku, the scope of the definition broadened. Today, in the US, it can include the burning of horse hair or feathers against the piece, or in some cases it can include an obvara mixture4 to create more naturalistic patterns from where the burning occurs. When the hair burns, it smells absolutely foul. When the obvara burns, it smells like burnt toast. Both were combined with billowing smoke from the reduction containers and the slightly sulfuric smell of a gas kiln. I was thankful it was windy in that moment.

I particularly liked how the burnt bits above the main brown area of the obvara vase look like pine trees sticking up above the foliage of a forest. Later obvara dunks for other pieces had lighter browns when the mixture was not as homogenous at time of dunking, or in one case, it looked like a coral growth pattern up the side of the piece because the burning was localized to such specific areas.

I’m happy that we were able to take a day and go attend this workshop, and I’m hopeful that we’ll go back soon. I’m very happy with the pieces we returned home with, and now that we know how the various techniques look, it’ll be interesting to apply that knowledge and try to make something even more intentional next time.

Footnotes

-

When it’s in the severals of hundreds, it doesn’t matter as much which temperature scale you use. ↩

-

I’ve only ever seen it be placed into a metal garbage can. It’s one of the most exciting reasons to have a trash fire I’ve seen yet. ↩

-

This tends to be stuff like newspaper and woodshavings, though we also had barley seeds at this workshop. Other folks will throw in banana or orange peels, copper wire, and other things that melt or burn in interesting ways. ↩

-

Obvara is a mix of water, flour, yeast, and sugar. Some folks said you could probably spray beer directly onto the piece too and have some similar effects, but the bucket definitly helped the uniformity of the thermal reaction. ↩