posted by on December 8, 2024

In college, I spent a summer doing an independent study on how to make a robot bird that could fly. I watched documentaries, I did wikipedia deep-dives, I learned musculoskeletal structures and how they varied across species, I studied the modes of flight among differently sized and shaped birds, and I looked at the state of the art in ornithopter-design at private robotics companies. I learned that the reason predatory raptors like vultures are often depicted circling overhead in cartoons was to do with the ways that they used static soaring from thermal gradiants to gain altitude without using much of their own energy. I also learned that the bird with the largest wingspan in the world1, the albatross, used dynamic soaring to build speed from taking advantage of the boundary of wind gradients. I planned to use slope soaring as a means to achieve lift, since my college had a gradual slope with a prevailing wind, and because it seemed to have the least amoung of moving parts.2

As soon as I learned about the albatross, I was compelled: it’s a bird that has trouble taking off compared to other flight-ful birds with smaller wingspans. For this reason, albatrosses tend to live in areas with high prevailing wind-speeds — often islands with sharp inclines at the coast. I read that one of the main areas in the world that has both albatrosses and everyday human populations is New Zealand. Since then, I’ve always wanted to go and see one. When we were planning our trip to Aotearoa New Zealand, seeing wild albatrosses was one of the things on my list that I had to do.3

To understand why albatrosses are viewable at the tip of the Otago Peninsula, it helps to understand the history of the area. Per previous posts, Aotearoa was and is a sanctuary for birds because of how and when it was formed geologically. The Māori established the Pukekura pā4 on the hilltop at the end of the Otago peninsula in the mid 1600s. Skipping forward a few centuries, Dunedin5 was founded by Scottish colonists in the mid 1800s. After gold was discovered in 1861 at Gabriel’s Gully, ~80km west of Dunedin, the ensuing gold rush exploded the population. By 1874, Dunedin was the city with the largest population in New Zealand. In the 1880s, fears rose that the Russian government might attack New Zealand at any moment.6 With Dunedin as a major target that needed defending, the Pukekura pā was torn down and the peninsula tip was cleared of any remaining trees to make way for Fort Taiaroa, along with an Armstrong Disappearing Gun inside it.

The first albatrosses seen in the area were in the late 1910s. Wildlife experts believe that the clearing of forests and removal of any predators, combined with human-led displacement of albatrosses at other islands nearby to New Zealand is what led them to begin nesting by Fort Taiaroa. Dr. Lance Richdale7 was the man credited for helping establish protection for the albatrosses at Taiaroa Head. Part of these efforts eventually included the Royal Albatross Centre and turning the entire Taiaroa Head area into a predator-free zone. Doing so has made it an area where a number of other endangered bird species can roost safely.

The life of a northern royal albatross like the ones I saw starts when two albatrosses mate8 and lay an egg. The chick is taken care of by its parents, who alternate staying with the chick to protect it. As it reaches adolescency, chicks will begin the 1000km/day journey over the Pacific Ocean towards the West Coast of Chile. Along the way, these albatrosses also use slope soaring off of the ocean waves themselves as a way to further conserve energy. They drink salt water and their bodies process the excess salt out of it, leading to the remainder coming out the tube-shaped nostrils, down the beak, and off the curved tip as waste. The tubular nostrils are also able to smell their prey from great distances. For Northern Royals, their diet is 80% squid, but generally any small ocean animal near the surface is fair game. They’ll make the return trip to Aotearoa and begin mating before continuing to do this commute back and forth pretty much every year for the rest of their lives.

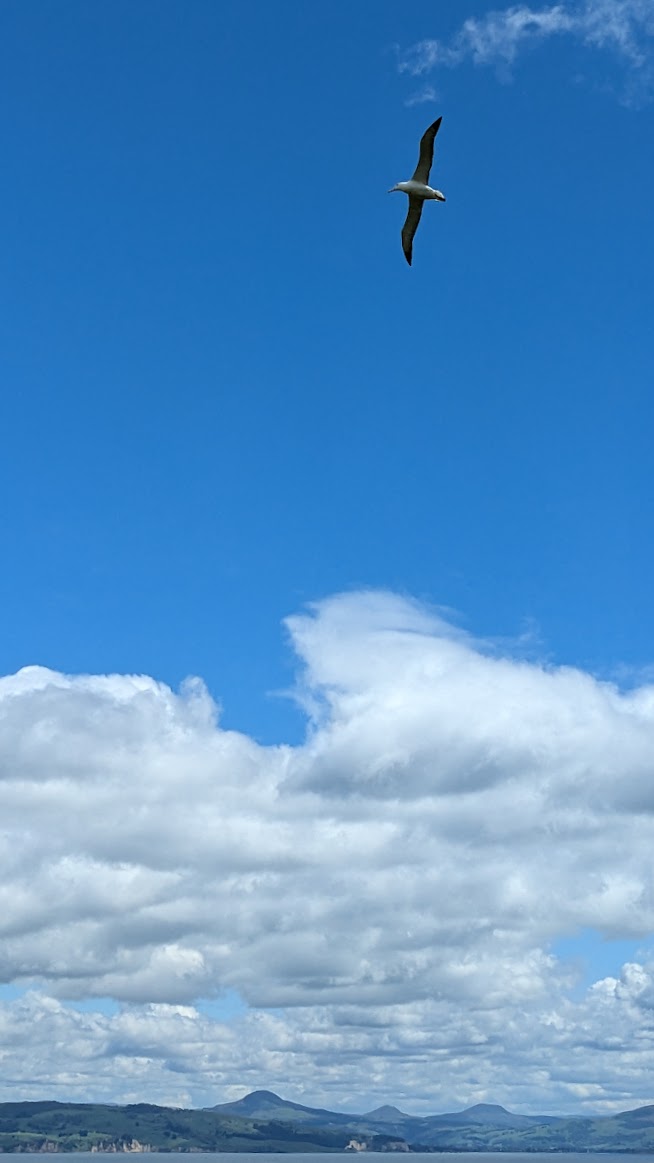

I can’t describe how nice it was to finally get to see the albatrosses in real life after all this time. When we first arrived at the viewing area of the Centre — a small windowed building on the top of the hill — we could see about three birds sitting by their nests in the grass below. I made quiet peace with the fact that this would be all we got to see of them, and through the binoculars it was really neat to see their feathers and bills as they looked around. But the real highlight for me was when, out of nowhere, we spotted a pair of albatrosses repeatedly soaring by before they too landed to begin nesting. It was exhilarating to see them actually flying in real life.

Footnotes

-

Ranging from wingspans of 2.5–3.5m (8.2–11.5ft) depending on species. ↩

-

I unfortunately bit off more than I could chew with that project, and never got to a completed flight attempt before running out of time in the class. The knowledge has stayed with me, though. ↩

-

Others included in no particular order: 1. See kiwis, 2. Ride the TranzAlpine train, 3. See Hobbiton, and 4. Go to Milford Sound. All of these are pretty standard tourist things to do there, so there’s a lot of readily-made itineraries built around them. ↩

-

In this case, a settlement on a hill defended by palisade walls and barriers, though there are various other meanings and usages in other contexts. You can read more about this history of this particular one at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03036758.1978.10429379 ↩

-

Dunedin is actually Scottish Gaelic for “Edinburgh,” and many of the street names and placements were just borrowed directly from the layout of Edinburgh. ↩

-

There was never any attack. ↩

-

The wildlife experts on our tour at the centre showed us a delightful number of photos of Richdale being bitten/mouthed by the bills of albatross on his clothing or hands over the years. ↩

-

Usually for life. There tends to be a whole unique language of both sounds and ways that albatross pairs like to squawk and click-clack their bills together that helps them find each other year after year. That being said, there are records of one member of a pair dying or not coming back to the area during breeding season and then the other moving on to find a new mate. The oldest on record was named Grandma and wound up mating with three different birds across her 60+ year lifespan, including one at the age of 62 in 2021 before she passed. ↩